One of my favourite aspects of studying the Bible in seminary is its literature-ness. All that stuff I learned in high school and university English classes is in there in spades. I may not have noticed it because the material was often presented as moral stories, not masterful literature designed not only to teach but also to engage with entertaining flair.

Obviously that rattles some cages, reading Scripture as “entertaining”. Fear not: “entertainment” doesn’t take away from but only augments its power and influence. Serious artists who create visual media to get significant messages across want the same said of their mediums and forms: entertaining and deeply meaningful.

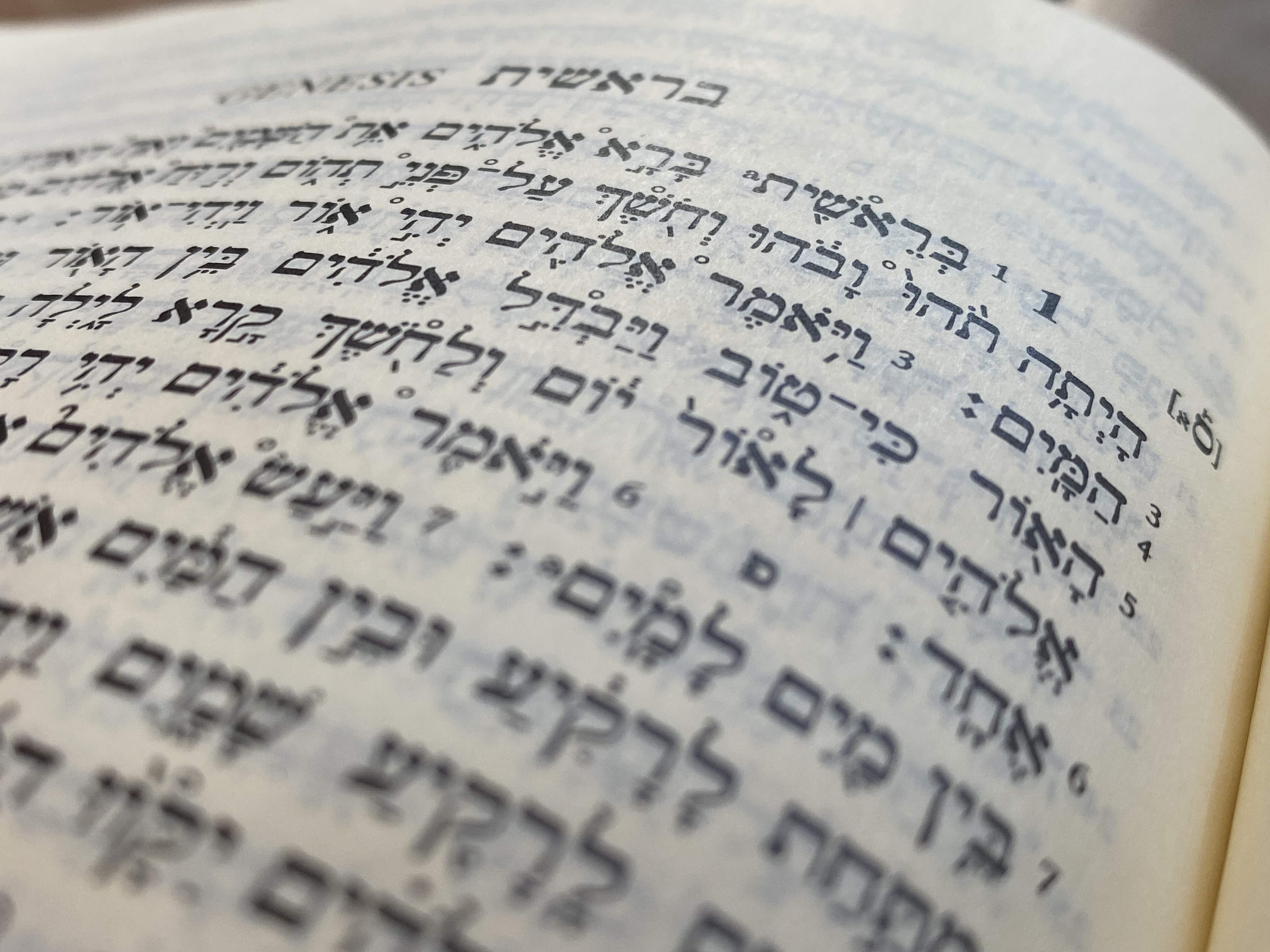

Consider the Jewish and Christian Scriptures put together (Old and New Testaments), in the Protestant-style sixty-six-book collection, or bibliography (get it? … bible…): sixty-six books telling stories using a massive variety of genres.

To name a few: non-fiction history, philosophical poetry, myth, epic battle, royalty romance, horror, dramatic tragedy.

None of the stories actually flatly conforms to a single genre. The mix is masterful. However, each narrative is often so short compared to modern narratives that their meaning can get missed in the quick read.

It was a different world when scribes and writing surfaces were expensive and hard to come by, and whatever got written had to fit inside a scroll’s length.

Talk about mastering conscise language and detail.

In modern Bibles, you’ll see books and chapters broken into headings that describe smaller sections. In narratives, these headings separate pericopes, which are akin to the term ‘beats’ in literature. Both can be roughly described as a ‘cohesive’ or ‘smallest’ unit of story.

A pericope or beat allows for a deeply satisfying rhythm: an up, a down. Positive emotions, negative emotions. Hope, despair. Building expectation, crushing expectation.

It’s intriguing that in modern English translations, the Old Testament ends with the prophets and an overall desperate, despairing sense: Israel has not achieved peace in the promised land and is under judgment (it’s more complex, but let’s allow for this much).

In the Jewish order of the Old Testament, the last book is 2 Chronicles, which ends with Cyrus decreeing that Jews may return to the promised land: a positive, hopeful sense. Which differed from the modern, “Christian” order of the OT books that ends with Malachi and a hope for something not yet manifest.

Intriguing how the book order in a collection leaves you with a particular feeling. The order means something to the reader.

With all these pericopes and genres and books in the Bible, there’s an incredible unity unlike any other collection of literature in all of the world’s history. This collection involves dozens of books and authors and editors over 1500 years of the that consistently agree and testify to a single reality even as they work out its details in different ways. They didn’t regurgitate earlier writing like parrots but added additional experiences that agreed with past testimony of reality.

And out of this unity, you get the Bible’s main characters, and no, the answer isn’t an automatic “Jesus”.

The main characters are God and humanity. If we summarize humanity as ‘Adam’ the way the Apostle Paul did (e.g. 1 Cor 15:22, 45; Rom 5:14), then we have to realize for our modern minds that the name Adam represents humanity, plural: Adam and Eve, she and he, both his and her faults. They together.

With the unity comes the image of a tapestry being woven to explain God and humanity as best as possible in a limited space. Robert Alter in The Art of Biblical Narrative points out “how brilliantly it has been woven into a complex artistic whole.”

But it’s an incomplete tapestry.

The bibliography actually leaves us dissatisfied and questioning so many things. Are you questioning? Good! It drives us to willingness to engage the bibliography’s master Source, Author, Editor and Publisher for how this bibliography’s part of the tapestry relates to the in-process part of the tapestry we’re living out now.

A good novel makes promises to the reader at the beginning that it fulfills by the end. Excellent stories involve a peace broken by an inciting incident—enter the serpent—and a descent into disorder that needs dramatic repair.

So we keep in mind reading the Bible’s entire collection that the authors are seeking out that repair. Where’s that peace? Who’s going to bring it? How is it even possible and why do we even keep hoping for it? It’s a deeply human, very real problem for us individually and communally.

We get to Jesus and discover a ridiculous interruption in the disorder with incredible order restored: he heals the sick, raises the dead, casts out demons, cleanses lepers, loves the outcasts, stands against the religious oppressors, turns death to resurrection in his own body, and authorizes his followers to follow his lead. He earns what we crave and then offers it without payment: life without death—relieved of our grief—having made himself available in the flesh to be scapegoated, absorbing all the violence of human wrath, and overcoming its effects.

But it’s only a partial restoration: humans at large don’t yet physically manifest that life without end. The bibliography ends on that note, requiring a sequel: breaking out of our current prisons of all shapes and sizes into an eternity peace.

Genius literature!

Holy Spirit, give us joy and satisfy our cravings with genius literature.

Leave a comment